Vice posted an article last week on one of the most influential cold cases in British history that was attributed to "witchcraft" and somehow went on to fuel a pop culture sensation. In 1945, a 74-year-old farm worker named Charles Walton was found murdered outside the town of Lower Quinton in England. Because his body was found in an odd position, police decided that occultism had to be involved - and the media ran with it. Let's just say that the United States in the 1980's and 1990's wasn't the only place where law enforcement liked to connect anything remotely weird at a crime scene with witchcraft, magick, satanism, or whatever the paranormal flavor of the day happened to be.

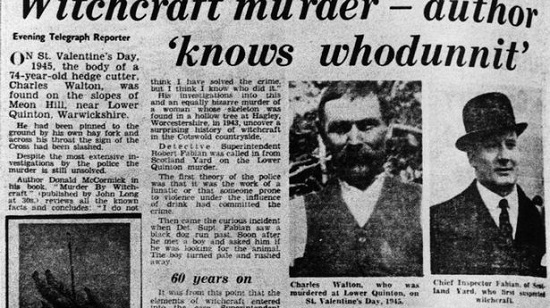

Lower Quinton subsequently gained a new level of media attention, and the newspapers relished in turning the story of Walton’s death into an Agatha Christie-style murder mystery about backward-thinking, sun god-worshipping rural folk. Salacious headlines about human sacrifice were abound, and the local Coventry Telegraph referred to the case as a “whodunnit witchcraft murder”.

“The then 87-year-old Margaret Murray [author of the popular but much maligned The Witch-Cult in Western Europe: A Study in Anthropology] believed the Walton murder was likely a ritual act, performed with the purpose of replenishing the soil,” explains Darren Charles, a historian from the Folk Horror Revival project. Touching on some of the wilder rumours that circulated, he says: “Apparently the year before Walton’s death proved to be a difficult harvest and the beer brewed from those crops was undrinkable. Walton was seen as an unusual fellow, who had bred Natterjack toads in his garden and tamed wild dogs with just his voice.”

Although this might all sound far fetched as a motive for murder, Charles says it was much more logical in the context of the time; of a remote region re-connecting with its ancient superstitions amid the dread and fears of World War II. To some locals, unsure of the future, looking backwards, and outside of the Christian church for philosophical guidance, was far more appealing. “Near [to where Walton’s body was found] is the Rollright Stones [an ancient stone monument] and the Burhill Iron Age Hill Fort, which give the whole region a sense of being ancient, magical, and strange,” adds Charles.

The crime remains unsolved, giving it a certain mystique to filmmakers, and arguably acting as a nucleus for the booming folk horror genre. David Pinner’s 1967 novel Ritual was loosely based on the Walton murder. When it was adapted into 1973 cult classic The Wicker Man, the idea of a rural town harbouring pagan beliefs and merrily sacrificing dissenters solidified itself as a narrative device in horror cinema, with a through line that can be traced all of the way to Ari Aster’s Midsommar (2019) and Ben Wheatley’s In The Earth (2021).

And here's the thing - it's very unlikely that Walton's murder had anything to do with magick or witchcraft, just like the also-famous and also non-occult murder of Jeannette DePalma that took place in the United States in 1972. As in the DePalma case, police looked at the Walton crime scene and decided that there had to be a sinister occult motive behind the crime. This was because he was killed with farm implements (that he might have just been carrying with him, since he was a farm worker) and had a mark like a cross in his chest (when any two intersecting cuts form a cross).

The fact is that "occult crime" and especially "occult murder" is incredibly rare. You do occasionally find crazies who are into occultism commit murders, like the Danyal Hussein case from 2020, but you won't find large groups or cults or sects or whatever involved. There are a couple of reasons for this. First of all, it doesn't work. Murdering someone to fuel a spell is incredibly inefficient and ineffective. Hussein "sacrificed" two women with the intent of winning the lottery. Of course he won nothing, because that's not how you cast a powerful spell. I'm not going to go into all the technical reasons why in this article - for now, just take my word that you'll get far better results using other methods.

The real issue seems to be that for the media, one occult murder is enough to speculate that there are millions of occult murderers out there and that they pose a real danger to significant number of people. This fueled the "Satanic panic" conspiracy theories of the 1980's and 1990's and has wormed its way into today's "QAnon" nonsense. I said it before and I'll say it again - there aren't even very many occultists out there, let alone occult criminals. What we do is very much a niche interest without much mainstream appeal.

If there were millions of practitioners out there, folks who sell magick books and magick supplies would all be rich and prosperous. Meanwhile, what I see in the real world is limited book sales, and magick suppliers getting into online spats because they're basically fighting over the same tiny pool of customers. The math itself doesn't support some kind of murderous occult underground, a handful of cases here and there notwithstanding. And just like the Walton and DePalma cases, I suspect that many of the cases that make up that handful never had anything to do with occultism.

So what really happened to Charles Walton? The article goes on.

The idea of people in the sticks being more susceptible to demonic influence became more and more prominent in cinema across the 1970s. However, Maria J. Pérez Cuervo – a writer specialising in archaeology and the creator of Hellebore zine – insists these stories were also being told when Walton was alive in the 1930s and early 1940s. “The link between rural communities, pagan beliefs, and ritual sacrifice was very much in the zeitgeist when Walton was murdered, largely due to the popularity of The Golden Bough by Sir James Frazer, a direct inspiration for both The Wicker Man and Robin Redbreast,” she says.

“Frazer had traced a common template for a series of myths and rituals from around the world, concluding that they were part of a widespread belief in a solar god-king whose ritual killing ensured the fertility of the land, and who would be reborn again in the spring to start a new cycle. His work suggested that the apparently inoffensive rituals performed in remote rural corners in Britain were actually pagan survivals. This proved inspiring for many authors working on genre fiction, and also had an impact on the way Walton’s murder was reported – and therefore in how the case is remembered now.”

It's an assessment criminology professor David Wilson very much agrees with, referencing Dennis Wheatley’s 1934 novel The Devil Rides Out as another example of a horror story that lurked in the public subconscious around the time of the murder. The number one suspect regarding Walton’s death, Alfred Potter, was a farmer involved in a financial dispute with Walton.

All evidence suggests that occult murders are vanishingly rare. Murders over money, on the other hand, make up a pretty significant proportion of such crimes. To me this whole "zeitgeist" Cuervo is talking about sounds like little more than prejudice against "simple country folk" who were too stupid to see past their superstitions. It should come as no surprise to anyone that in reality, such people were plenty smart and certainly wouldn't go around killing people based on outlandish, misguided beliefs.

Oddly enough, the "QAnon" and "Illuminati" nonsense we are seeing today completely inverts this script. Instead of "simple country folk," the conspiracies now center upon the incredibly wealthy, who do legitmately hold outsized influence in business and politics. But hardly any of those folks are occultists either. If you have enough money, you don't need magick to get what you want - you can just hire somebody to get it done. And the fact is that people who amass that kind of wealth rarely have time to think about much besides money and commerce.

The next time you see anyone in the news talking about "occult murders" or "occult conspiracies," take it with a grain of (purifying) salt. In some cases like the Hussein case, the occult ties are obvious and can't be denied. On the other hand, if the signs of occultism that are being talked about seem sketchy, like sticks or rocks at the crime scene that look odd, or a couple of crude graffiti pentagrams, or a cut on the body that looks unusual, it's very unlikely that you're looking at an occult crime. You're probably looking at a regular crime that happened in an unusual place or under unusual circumstances.

No comments:

Post a Comment